The Winning M&A Advisor [Vol. 1, Issue 4]

Welcome to the 4th issue of the Winning M&A Advisor, the Axial publication that anonymously unpacks data, fees, and terms…

Marc Andreessen, famous entrepreneur turned venture capitalist, famously asserted in 2011 that “software is eating the world.” More recently, there is a growing chorus of pundits and practitioners talking about the impact of automation and artificial intelligence (AI) across the financial services industry.

Some of this has turned out to be largely overblown, at least in the near-term. Just a few years ago, many predicted that robo-advisors would completely eliminate human wealth managers — but today, that market is evolving slowly with human wealth managers very much in demand (and in many cases companies offering both human and robo-advisors under one roof). Other predictions have come true. Today, the floor of the New York Stock Exchange is nothing more than a PR stunt — all equity trading is electronic and market-makers have been replaced by machines.

However, amidst all this chatter, there’s been little coverage on the impact of AI, software, and automation within the arcane and relationship-driven world of investment banking and M&A. The coverage that does exist mainly highlights large-cap players: Reuters put out a story on Goldman Sachs’ efforts to automate certain aspects of how their M&A bankers execute deals, and Bloomberg published a piece on how JP Morgan has marshaled in-house engineers to parse financial deal data, replacing 360,000 hours of lawyers’ fees. As is common, there has been no meaningful coverage on the implications of software and automation on middle market investment banking practices.

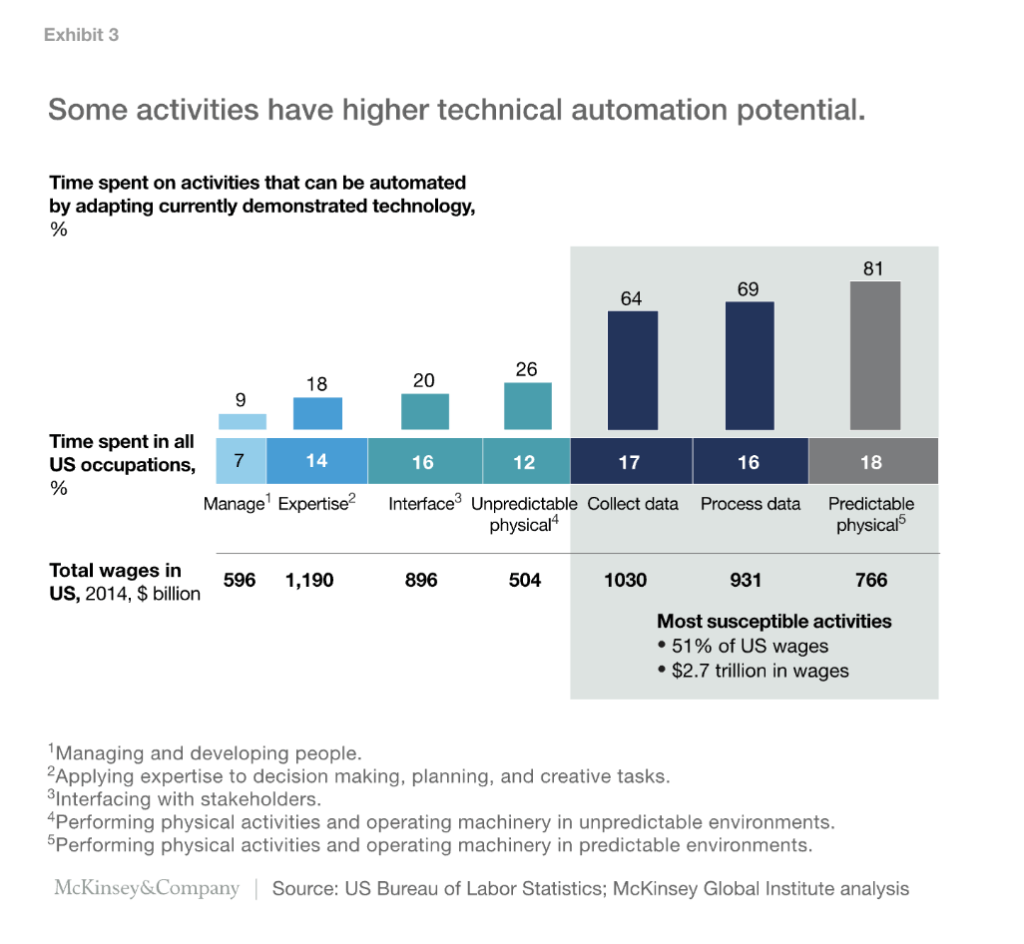

If you ask most any investment banker what they hate most about their job, especially the junior roles, the answer usually revolves around data collection or data processing. The drudgery of searching for data, pulling it, cleaning it, fact-checking it — these are time-intensive, maddening, and required tasks in investment banking, and they are shouldered by the junior ranks. These tasks are even more pronounced in the middle market, thanks to the sheer number of potential buyers per deal and the relative lack of transparency compared to the large-cap market.

The drudgery of searching for data, pulling it, cleaning it, fact-checking it — these are time-intensive, maddening, and required tasks in investment banking, and they are shouldered by the junior ranks.

The good news for these bankers is that these tasks likely won’t be under the purview of human employees for long. According to research from McKinsey’s Global Institute, tasks relating to collecting and processing data are almost the easiest types of activities to automate using currently available technology.

At some middle market investment banks, this transition is already well underway. “Twenty of our 22 employees are investment bankers,” says Ken Marlin, founder and managing partner of middle market investment bank Marlin & Associates. “We outsource everything else: payroll, benefits, accounting,

technology, etc. Data gathering, data processing, and data modeling aren’t really the source of distinction anymore. The core of the job is about intellect, intuition, and creativity.”

The (perhaps) bad news for junior bankers? This automation may render meaningful portions of their job responsibilities moot. In a world where data collection and processing is approaching full automation, what role do these understudy bankers play?

George Lee, CIO of Goldman Sachs, insists that investment bankers — junior or not — aren’t going away. “Our strategy is to elevate the activity and impact of bankers,” he told Bloomberg. “Not replace it.”

Taylor Curtis, Managing Director at MHT, agrees. He says that no matter how good the technology gets, there is always more — or different — work to be done. “Before we had Microsoft Excel, were we using handmade spreadsheets? Yes, and because they took forever, we could only get them so good. When Excel came along, we didn’t go home at 5 o’clock — we cranked out more models, with greater accuracy and more and more scenarios and sensitivities. Same goes with Capital IQ. Not a single analyst on my team knows how to create comps from scratch like I used to do — but they spend all of their surplus time and more selecting and tuning those comps.”

As the role of investment bankers in general is elevated, says Curtis, expectations for the junior ranks will both change and rise. Rather than rely on junior bankers to crunch numbers and search for esoteric data, senior bankers will look for young hires with a more well-rounded set of skills.

“Ten out of ten times, I will trade off lower quantitative and technical skill for someone I feel is going to be more creative with the data, build out better stories and narratives for our client, and be more client-ready on Day 1. The modeling is still critically important, but I’ll take that trade-off every time,” says Curtis.

Certainly food for thought for the next generation of investment bankers.