SaaS Valuations: How to Understand Your Business’s Worth (and Get the Best Exit)

Learn how SaaS companies are valued and how to maximize your deal outcomes with industry-specific insights from a top SaaS M&A advisor.

Tags

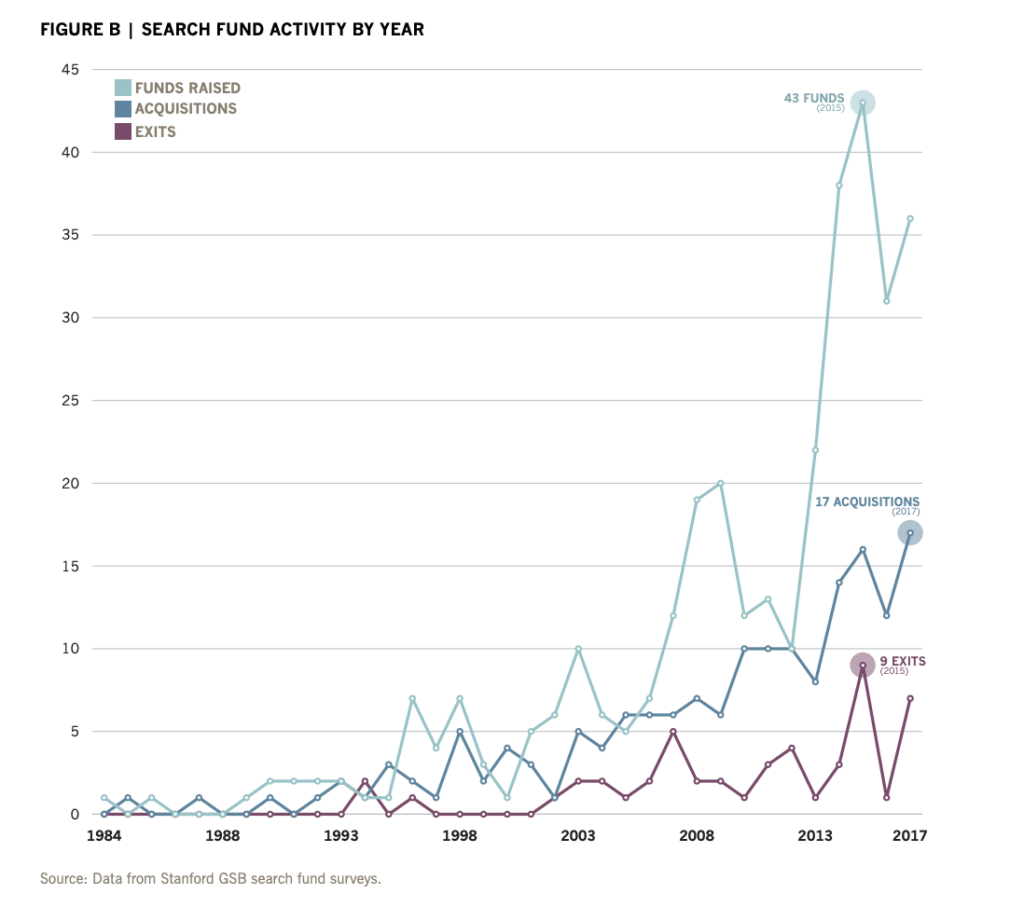

Today, the number of active search funds is at an all-time high, according to Stanford’s 2018 Search Fund Study. A record 17 companies were acquired by search fund entrepreneurs in 2017, according to the study. Since the first search fund was formed in 1984, investors have put $924 million of equity capital into these investment vehicles, with a total equity value of $5.7 billion for investors and $1.5 billion for entrepreneurs.

In the traditional search fund model, one or two people — typically recent MBAs — raise capital from a group of investors to find, acquire, and run a private company.

Though search funds are a niche investment model to be sure and these are small numbers, they represent significant growth. The chart below, from Stanford’s study, shows the steady rise in funds raised and acquisitions over the past several years (the number of exits has not followed the same trend).

As the number of search funds has increased, alternatives to the model have emerged. One is the so-called search fund “accelerator,” in which the aspiring entrepreneur is employed by a single firm which provides capital and advises on the search (rather than the searcher amassing a group of investors to fund their search as is in the traditional model). This is one form of what’s referred to as the “captive” model, in which searchers are funded by a single source.

Search fund accelerators typically recruit a number of searchers each year, giving each member of the cohort the opportunity to share resources as well as providing general education and advising services.

“We’re halfway between a search fund and an operator-centric private equity fund model,” says David Slenzak, Co-Founder and Managing Partner of Broadtree Partners. “All our searchers are employees of Broadtree Partners and get economics in their deals very much like a traditional search fund.” Broadtree raises money from LPs to back its organizations, and the searchers go back to those same LPs for the equity capital on each of their deals.

“We have the ability to go beyond our LP pool for gaps if those exist,” says Slenzak. Each year, Broadtree brings on around six searchers to join the team. The firm currently has 10 searchers on board.

Slenzak acquired a Charleston-based healthcare technology company, Implementing Technologies, via a search fund in 2010 and successfully exited the company in 2016, the same year he founded Broadtree. “I came up with the model for Broadtree based on the pains I experienced when I was a searcher. I had to recreate the wheel — create my own CRM system, develop my own list of contacts and targets, contact people my colleagues had already contacted who were not useful, make the mistakes my friends had already made.”

At the same time, Slenzak found other searchers — who soon became his friends — to be highly collaborative. “It’s not a competitive dynamic. Everyone wanted to share their experiences and best practices. I saw an opportunity to formalize some of that.”

Timothy Bovard, the founder and CEO of Search Fund Accelerator (SFA), came to a similar conclusion after doing extensive research on search funds as a professor of entrepreneurship at INSEAD. “Over 30% of searchers fail to acquire a company in two years, and then there’s another 28% who buy a company, but earn zero money. You juxtapose that with the investors who are, in most cases, making phenomenal returns. The traditional model is very much tilted in favor of investors.”

Bovard saw an opportunity to provide searchers a sense of support and community, much like startup accelerators like Y Combinator, which bring entrepreneurs together for a set of period of time, providing resources, mentorship, and access to investors.

Since its founding in 2015, SFA has recruited a class of 4-5 searchers annually and is in the process of recruiting up to seven searchers for next year. SFA has a pool of committed capital to fund searchers’ acquisitions.

Much of their value-prop centers around helping searchers optimize their processes and find companies that are the right fit for their skillset. “We put them through a three-week bootcamp where we teach them how to search and get the search up and running at full speed. For a traditional searcher, it may takes months of trial and error to get to the same level.”

The things that they go over range from brass tacks strategies like best practices for executing a direct marketing email campaign in a proprietary search process to more abstract lessons on how to think like an investor, says Bovard. “Often searchers find a company and become infatuated with it, but what they really need to do is think dispassionately and put themselves in the shoes of a third-party investor. It may be a great business if you’re the owner, but is it a good business to invest in?”

It is too early to know whether this alternative search fund model will help combat the high failure rate of traditional search funds. But if it does, it may be because these firms provide an additional layer of scrutiny on the searchers themselves, only accepting those who they are confident will be successful in the CEO role.

“We spend hours talking to potential searchers, getting to know them first as people,” says Bovard. “We’re interested in their formative years and their values, not just the jobs they’ve had. We do look at management experience, but we also look at charisma, analytical skills, intelligence, reasonability ability. We look for people who’ve failed and can articulate how they picked themselves back up and how they grew.”

Maturity and a sense of trust is key. Often their relationship with the searcher/CEO will extend 10 years or longer — “longer than many marriages,” Bovard jokes.

Broadtree also tries to ensure searchers are in it for the right reason, says Slenzak. “As more people look into search funds, it’s become a shiny object for some people. We have maybe a dozen interviews with the people we bring on. We try to find folks who truly want to become operators and aren’t misplaced deal guys.”

Obviously, the accelerator model is extremely hands-on when it comes to screening candidates. For some proponents of traditional search funds, this is anathema to the original model, which inherently rewards individuals with the desire and capability to self-select, raise capital for the search, and execute on the acquisition (not to mention run and ultimately exit the acquired company). “The traditional search fund model is the best way I’ve seen for an individual to create value while incentivizing alignment between the searcher and the investor. The traditional model attracts true entrepreneurs who would prefer to solve problems on their own rather than turn to a bureaucracy,” says one former searcher turned investor in search funds.

So far, Search Fund Accelerator says it has seen promising success in the model. All of its 2015 and 2016 searchers have bought companies, save for one 2016 searcher who is about to go under LOI.

After an acquisition, SFA’s role transitions to one more typical of a PE firm, albeit with more informal dialogue and support. “One of us is usually on the phone with our new CEOs every week in the first year. We don’t email and say, ‘When can we find time to talk?’ We just call each other. I don’t email my wife to find out when we can speak. It’s a much more fluid, friendly, supportive relationship than a typical investor-operator relationship.”

The searchers also continue to collaborate as they transition into their new roles. The cohorts have internal messaging channels and communicate frequently. This sense of community is amplified by the fact that every SFA searcher owns a small slice of equity in the others’ companies, in addition to the equity they have in their own business — what SFA calls “the common fund.” Each class of searchers attends their fellow CEO’s board meetings. “They’re tied together in a sense financially, but beyond that they’re friends,” says Bovard. “They are there for each other.”