Add-On Demand in the LMM: A Data-Driven Look at Buyer Activity

Most successful businesses adopt both organic and inorganic growth strategies. And add-on acquisitions remain one of the most widely used…

Who are the most active software investors and advisory firms in the lower middle market today? In this report, we unpack insights from anonymized private transaction activity on the Axial platform to surface the network’s 25 most active software investors and 25 most active software advisory firms. In addition, we analyze the data to reveal which software sub-sectors are seeing the highest levels of current demand (rather than historical closure data) from financial investors and corporate acquirers.

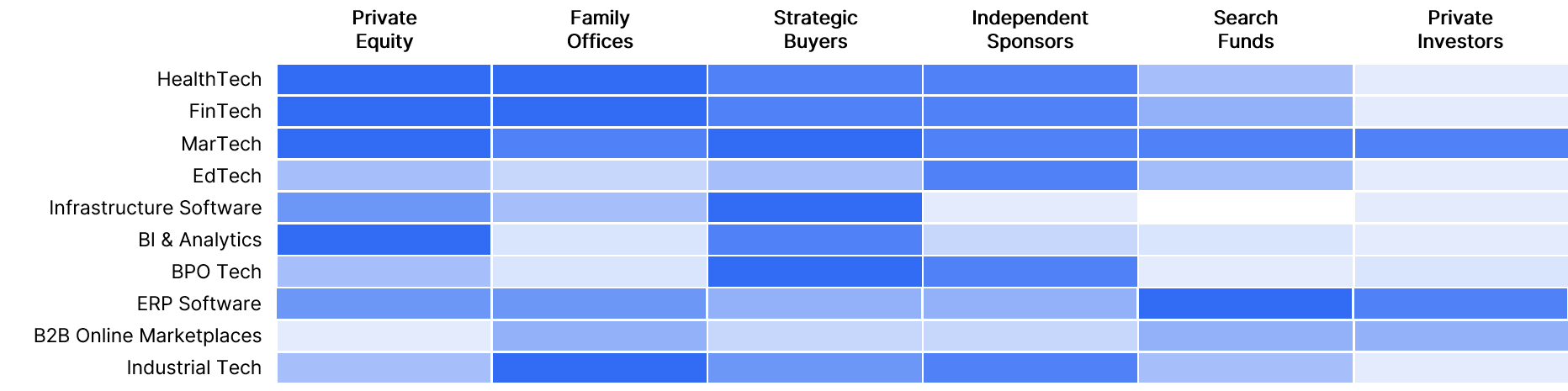

The market map above shows the top 50 most active firms — see the full list at the end of this article. The data driving the heatmap incorporates member closed transaction data, as well as Axial platform activity that assesses firms’ software experience and specialization benchmarked against 5,000+ of their peers. In addition to the market map, we’ve included a full report below with first-hand commentary and analysis from four of these top Axial members on sector trends and forecasts (below).

This is the second report in an ongoing series, and we’d love to hear your feedback. Email us at [email protected] If you have questions, ideas, or additions.

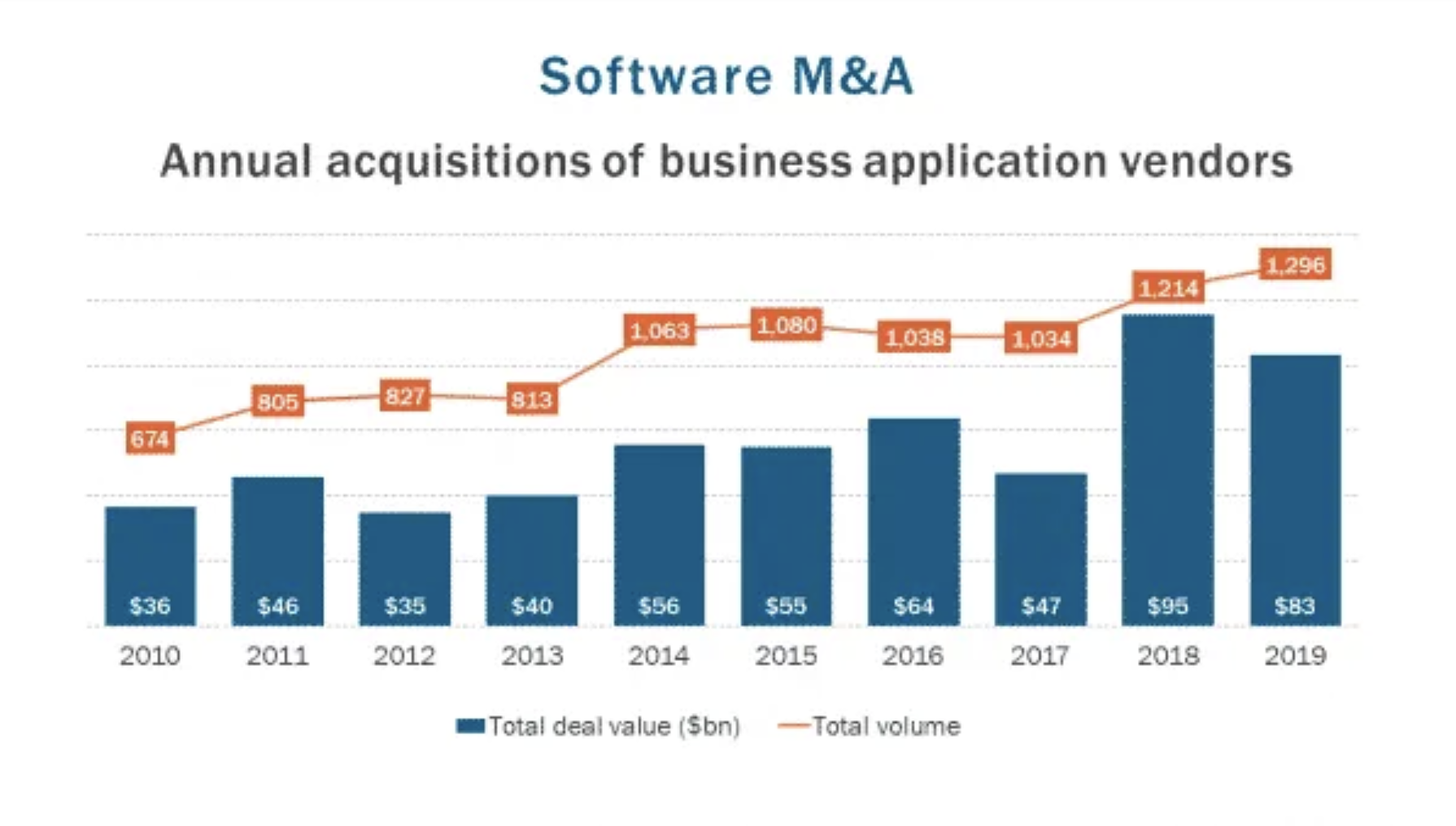

Software continues to be a growing segment of deal activity for lower middle market buyers and investors, and the data reveals an increasing number of smaller deals getting done in the space. Last year, the total number of software deals closed increased 6.75%, while average deal size decreased 18.6%, according to Solganick & Co.

The demand for B2B application software is the primary growth driver. According to the NPD Group’s 2019 review, software was the top purchase intention for small businesses last year, with 66 percent planning to spend on the category, up 7 percent from 2018. Software sales also grew at a 10 percent compound annual growth rate from 2015 to 2018 versus non-software categories, which grew just 3 percent during the same period.

Which software sub-sectors are seeing the most buyer and investor interest in the lower middle market? We analyzed mandates from over 1,600 buyers on Axial, and ranked each sub-sector according to its relative share.

Rank Sector Percent of Buyer Mandates

| Rank | Sector | Percent of Buyer Mandates |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Healthcare Technology | 9.75% |

| 2 | Financial Technology | 8.40% |

| 3 | Marketing Technology | 7.04% |

| 4 | Education Technology | 6.77% |

| 5 | Infrastructure Software | 6.51% |

| 6 | BI & Analytics | 5.69% |

| 7 | BPO Technology | 4.60% |

| 8 | ERP Software | 4.06% |

| 9 | Industrial Technology | 3.93% |

| 10 | B2B Online Marketplaces | 3.79% |

Three of the top four sub-sectors, according to buyer demand, are vertical software business categories: healthcare technology, financial technology, and education technology. We examined why these areas in particular are most in demand and what top dealmakers are seeing in the space.

Technology demand heatmap by firm type and sub-sector

Investors’ interest in these three verticals can in part be attributed to the market size and growing demand within each respective market. Healthcare, financial services, and education organizations are expected to be some of the biggest investors in enterprise IT over the next five years. The global healthcare IT market size was valued at $125 billion in 2015, and is expected to reach $297 billion by 2022, with a CAGR of 13.2%, according to Valuates Reports. The global fintech market was valued at about $127.66 billion in 2018, and is expected to grow to $309.98 billion at an annual growth rate of 24.8% through 2022, according to the Business Research Company. Meanwhile, the global edtech market is expected to reach $277B+ by 2022, with a CAGR of more than 15% over the next five years, according to Solganick & Co.

The coronavirus pandemic will likely impact these predictions – but not necessarily negatively. According to a recent Reuters report, “many companies actually intend to accelerate [tech] spending to support thousands of employees that now have to work from home as the majority of governments around the world order national lockdowns.”

IT spending has been rampant in healthcare, finance, and education alike in recent years, in large part because long-time players in these industries have been slow to adopt technology and are now investing heavily to catch up. While this presents a substantial opportunity for smaller software companies to sell lucrative subscriptions, it also means they are subject to bureaucratic approval processes. The snail’s pace at which many of these larger companies evaluate and purchase subscriptions to new technologies can put growing software businesses — many of which generated the lion’s share of their first few years of revenue from nimble startups & fast-moving early adopters — in a significant cash flow bind.

These enterprise clients may take months or even years to convert to customers. “Financial services, healthcare, and education systems are all notably slow,” says Aaron Solganick, CEO of investment bank Solganick & Co. “So, verticalized technology companies often get stuck in a no-man’s land where they have a lot of sales contracts that could potentially pan out, but they also need to stay afloat while those contracts are being negotiated.”

For founders, “there tends to be a fairly low barrier to entry for these companies, so you can get them off the ground pretty quickly and begin building a meaningful business,” adds Palmares’ Mark Anderson, Managing Director at software and IT specialized investment bank Palmares Advisors. “Getting them to real scale is difficult given the competition and growth requirements for capital infusion. A lot of companies get stuck in a space where they’re big, but not quite big enough for [growth stage] venture capital.”

As in most lower middle market categories, the largest driver of M&A activity in these three vertical software sub-sectors is the abundance of targets and accompanying fragmentation. On the one hand, the trend of aging baby boomers without successors is particularly true in the software space: “Given how technical running a software company is, passing a business down to the next generation usually goes poorly,” says Timothy Goddard, EVP of Corporate Strategies at Corum Group — meaning most founders look to a third-party sale.

On the other hand, a substantial volume of sellers coming to market and companies seeking capital is derived from the flood of venture capital dollars entering the market, and the plethora of sub-scale businesses that those financing sources create. By the end of 2019, the VC industry deployed $136.5 billion in U.S.-based companies, surpassing the $130 billion mark for the second year in a row, according to Pitchbook. While VCs drive many of these companies from seed stage through series A and B , as these companies’ rates of growth start to diminish, they gradually transition into more suitable targets for lower middle market M&A.

Whether a team has bootstrapped their way to $5M – $25M+ in revenue or has reached that level in part due to capital infusions, companies nowadays are rarely sustaining enough growth to garner attention from growth stage venture capital firms and some private equity firms. “Venture capital firms are not the best fit for these businesses, given VCs’ aggressive growth requirements,” says Goddard. “Even if the businesses are growing 100% year over year, in many cases even that’s not enough for venture capital investors.”

According to Goddard, business owners are reciprocating with a growing disillusionment of the VC model as a whole. “In some cases that’s because the market isn’t a good fit for the VC model, and in others it’s just because they’re suspicious of the VC model in general — the risk versus reward — regarding how it plays out for the investors versus the founders.” As a result, many companies with moderate to strong growth profiles are pursuing alternatives to venture capital. “From a funding perspective, there’s a lot of white space for family offices and smaller PE firms,” says Palmares’ Anderson.

There are certainly some software companies that enjoy rapid or hyper-growth, defined by the World Economic Forum as having 20-40% CAGR or 40%+ CAGR, respectively. The majority of these companies will raise upwards of five or six rounds of growth capital until seeking a sale or an IPO. For the majority of lower middle market investors acquirers, however, these companies are almost certainly outside their purview. Instead, lower middle market players will likely look at companies in one of the following three stages of growth:

Companies that have good technology, but have struggled to build a business around it and are now looking to sell. They may have already raised a series A or B round, so there can be several million dollars invested in the technology, but all forms of debt or minority equity financing are not available given the lack of business model viability.

Companies that are beyond early stage — either having raised a Series A or B, or been bootstrapped and don’t have growth potential to raise venture capital — and have developed a solid product with flat growth or bleeding cash flows. Given mistakes in initial operating investments or the capital intensity of such businesses, they require a restructuring, change of control transaction, or flexible capital infusion to overcome the cash flow crunch. Any forms of financing with aggressive return expectations are not realistic options.

Growth stage or mature companies that have modest to substantial growth potential, but are not in hyper-growth. This group comprises “solid” businesses with mature and understandable unit economics, often run by either an aging baby boomer with no clear successor, or a couple of founders looking to find a strategic growth partner and take some chips off the table by selling a significant equity stake.

Stage 3 is where competition is most intense among middle market and lower middle market acquirers. These businesses are financeable, have mature unit economics, and have growth profiles that render them no longer attractive for VC or other forms of high growth capital.

Software entrepreneurs have a plethora of options in the lower middle market capital arena, including strategic buyers, private equity firms, family offices, independent sponsors, high-net-worth individuals, venture debt providers, and search funds. Below, we provide an overview of what the three top buyer types — strategies, PE, and family offices — tend to gravitate towards.

“Strategic buyers often look to buy a company for its technology offerings and capabilities — they want to incorporate those assets into their existing distribution channels,” says Palmares’ Anderson. “They don’t need to buy a business for its P&L, whereas a financial investor needs a business that is cash flow generating on a standalone basis.”

While strategic buyers are viable potential capital partners at every stage of a software company’s maturity, they are particularly interested in buying vertical software companies in order to add horizontal product lines and cross-sell new customers into their existing business. Companies in stage 1 — those that have developed a valuable product that is not yet necessarily a viable business — can be great fits for strategic buyers especially if the underlying technology is well-built and complementary with the acquirer’s existing offerings.

Large companies are also increasingly dipping their toes in the lower middle market. In fintech, for example, “large players like Fidelity National Financial and Finastra are definitely coming downmarket for both acquisitions and investments,” says Solganick. “Sky-high multiples — as much as 12x to 15x EBITDA — have been the norm for strategics across software industry sectors, until recently.”

“Financial investors are stepping up and becoming a lot more competitive with strategic buyers,” says Solganick. “Because there’s so much capital that has been raised by private equity firms, they’re bidding higher prices to win deals. The current Covid-19 environment has also curbed strategics from acquiring companies as they conserve their cash and implement cost controls. Financial investors as a result are scooping up companies that normally strategics would typically win.”

PE firms looking for platform companies will usually target businesses that are beyond the cash flow crunch and in a steady growth state (stage 3 above), looking to add fuel to the fire. But PE firms are also increasingly looking at smaller and smaller software companies (within stages 1 and 2) as add-ons, says the Corum Group’s Goddard. “These up and coming companies are selling earlier than they might otherwise, and cycles are moving quickly given PE-backed corporations are looking to put these disruptive technologies to work.”

“As a family office we have a competitive advantage over committed funds with aggressive time horizons that may not fall in line with the scalability and timeframe of the business,” says Kevin Fahey of Bluff Point Associates, a family office that invests exclusively in healthcare and financial technology businesses. “We can make investments in the first few years (i.e. lose money) as long as we are confident it will pay off down the line in terms of substantial growth by years five or six.”

Many family offices have found their niche in the technology space by focusing on companies experiencing the cash flow crunch (stage 2 above), especially those where the founders might want to stay on or where the growth prospects are more long term. Similar to venture capital firms in some sense, family offices can also be more flexible to write a smaller check, with an interest in seeing a path to put more money to work overtime. “We might start out with as little as a four, five, or six million dollar investment,” Fahey remarks. “But then over a two or three year period, we’ve invested up to $10 or $15M – enough capital where there’s a substantial ownership stake for both parties.”

Given the complexity of the industry and immense appetite for software acquisitions from middle market buyers, it can be difficult for business owners to navigate the universe of potential capital partners. We are seeing software entrepreneurs increasingly opt to enlist an investment bank, advisor or broker to generate competition in a process to yield an attractive valuation and find the right partner.

Corum’s Goddard remarks, “We are firm believers that valuation is driven by process. Bringing a diverse mix of buyers together drives substantially higher valuations in software M&A processes relative to other industries, especially if you find a buyer where the technology is going to be vital to their future, or they see an opportunity to make inroads into valuable underserved markets. Without a national or global process, you’re not going to realize the kind of value that you would otherwise.”

As many acknowledge, executing a well-run M&A process is not merely a function of achieving an optimal valuation — a business owner wants to find the right partner to grow with or continue their legacy. Solganick adds, “Very few sellers say, ‘I just want to get out and retire.’ That inherently affects the type of buyer that they ultimately choose to engage.”